How Is Easter Determined

Computus (Latin for 'computation') is a calculation that determines the calendar date of Easter. Because the date is based on a calendar-dependent equinox rather than the astronomical one, there are differences between calculations done according to the Julian calendar and the modern Gregorian calendar. The name has been used for this procedure since the early Middle Ages, as it was considered the most important computation of the age.

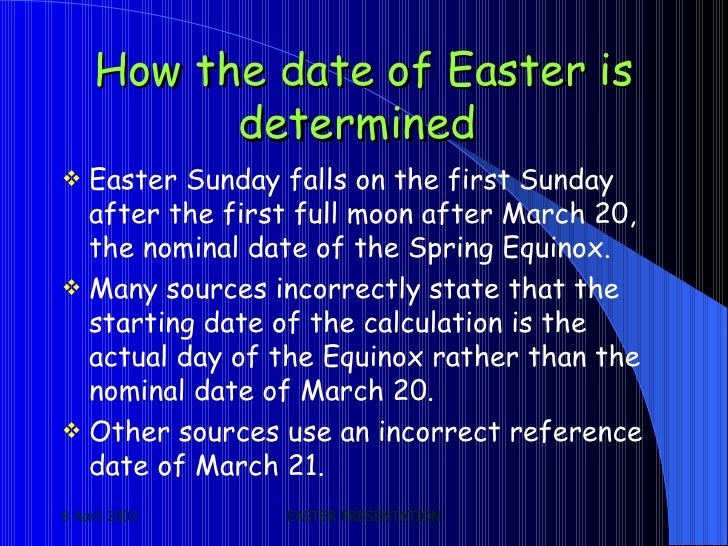

For most of their history Christians have calculated Easter independently of the Jewish calendar. In principle, Easter falls on the Sunday following the full moon on or after the northern spring equinox (the paschal full moon). However, the vernal equinox and the full moon are not determined by astronomical observation. The vernal equinox is fixed to fall on 21 March (previously it varied in different areas and in some areas Easter was allowed to fall before the equinox). The full moon is an ecclesiastical full moon determined by reference to a conventional cycle.[1] While Easter now falls at the earliest on the 15th of the lunar month and at the latest on the 21st, in some areas it used to fall at the earliest on the 14th (the day of the paschal full moon) and at the latest on the 20th, or between the sixteenth and the 22nd. The last limit arises from the fact that the crucifixion was considered to have happened on the 14th (the eve of the Passover) and the resurrection therefore on the sixteenth. The 'computus' is the procedure of determining the first Sunday after the first ecclesiastical full moon falling on or after 21 March, and the difficulty arose from doing this over the span of centuries without accurate means of measuring the precise tropical year. The synodic month had already been measured to a high degree of accuracy. The schematic model that eventually was accepted is the Metonic cycle, which equates 19 tropical years to 235 synodic months.

In 1583, the Catholic Church began using 21 March under the Gregorian calendar to calculate the date of Easter, while the Eastern churches have continued to use 21 March under the Julian calendar. The Catholic and Protestant denominations thus use an ecclesiastical full moon that occurs four, five or thirty-four days earlier than the eastern one.

The Sunday after the first moon following the vernal equinox is the date that Easter falls on. For example, the first full moon after the vernal equinox in 2014 came on Tuesday, April 15. This means that in 2014, Easter fell on the following Sunday, April 20. Note whether or not the full moon falls on Sunday. The basic rule for determining the date for Easter is that it is on the first Sunday after the first ecclesiastical full moon that occurs on or after March 21st. The beginning date, March 21st, was chosen because it is usually the vernal equinox (generally, the first day of.

The earliest and latest dates for Easter are 22 March and 25 April,[2] in the Gregorian calendar as those dates are commonly understood. However, in the Orthodox churches, while those dates are the same, they are reckoned using the Julian calendar; therefore, on the Gregorian calendar as of the 21st century, those dates are 4 April and 8 May.

- 3Tabular methods

- 3.1Gregorian calendar

- 4Algorithms

History

Easter is the most important Christian feast, and the proper date of its celebration has been the subject of controversy as early as the meeting of Anicetus and Polycarp around 154. According to Eusebius's Church History, quoting Polycrates of Ephesus,[3] churches in the Roman Province of Asia 'always observed the day when the people put away the leaven', namely Passover, the 14th of the lunar month of Nisan. The rest of the Christian world at that time, according to Eusebius, held to 'the view which still prevails,' of fixing Easter on Sunday. Eusebius does not say how the Sunday was decided. Other documents from the 3rd and 4th centuries reveal that the customary practice was for Christians to consult their Jewish neighbors to determine when the week of Passover would fall, and to set Easter on the Sunday that fell within that week.[4][5]

By the end of the 3rd century some Christians had become dissatisfied with what they perceived as the disorderly state of the Jewish calendar. The chief complaint was that the Jewish practice sometimes set the 14th of Nisan before the spring equinox. This is implied by Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, in the mid-3rd century, who stated that 'at no time other than the spring equinox is it legitimate to celebrate Easter' (Eusebius, Church History 7.20); and by Anatolius of Alexandria (quoted in Eusebius, Church History, 7.32) who declared it a 'great mistake' to set the paschal lunar month when the sun is in the twelfth sign of the zodiac (i.e., before the equinox). And it was explicitly stated by Peter, bishop of Alexandria that 'the men of the present day now celebrate [Passover] before the [spring] equinox..through negligence and error.'[6] Another objection to using the Jewish computation may have been that the Jewish calendar was not unified. Jews in one city might have a method for reckoning the Week of Unleavened Bread different from that used by the Jews of another city.[7] Because of these perceived defects in the traditional practice, Christian computists began experimenting with systems for determining Easter that would be free of these defects. But these experiments themselves led to controversy, since some Christians held that the customary practice of holding Easter during the Jewish festival of Unleavened Bread should be continued, even if the Jewish computations were in error from the Christian point of view.[8]

The First Council of Nicaea in 325 was primarily concerned with settling the Quartodeciman question (the practice of churches in the east of the empire of observing Easter on luna xiv, whichever day of the week it fell on). Probably because those churches which deferred the celebration to the following Sunday couldn't agree which Sunday to observe the Council thought it politic not to promulgate a canon on the matter but to come to an agreement. The terms of this agreement were set out by Constantine in a letter to those churches which were not represented.[9][10][11] The calculation was to be independent of the Jews. It was noted: 'When the question relative to the sacred festival of Easter arose it was universally thought that it would be convenient that all should keep the feast on one day .. for to celebrate the passover twice in one year is totally inadmissible .. By the unanimous judgment of all, it has been decided that the most holy festival of Easter should be everywhere celebrated on one and the same day.'

Hefele, History of the Councils, Volume 1, pp. 328 et seq., notes that the difference between the Alexandrian and the Roman computation continued after the Council. A Council was convened at Sardica in AD 343 which secured agreement for a common date. This soon broke down. As time went on Rome generally deferred to Alexandria in the matter.

The Patriarchy of Alexandria celebrated Easter on the Sunday after the 14th day of the moon (computed using the Metonic cycle) that falls on or after the vernal equinox, which they placed on 21 March. However, the Patriarchy of Rome still regarded 25 March (Lady Day) as the equinox (until 342), and used a different cycle to compute the day of the moon.[12] In the Alexandrian system, since the 14th day of the Easter moon could fall at earliest on 21 March its first day could fall no earlier than 8 March and no later than 5 April. This meant that Easter varied between 22 March and 25 April. In Rome, Easter was not allowed to fall later than 21 April, that being the day of the Parilia or birthday of Rome and a pagan festival. The first day of the Easter moon could fall no earlier than 5 March and no later than 2 April.

Easter was the Sunday after the 15th day of this moon, whose 14th day was allowed to precede the equinox. Where the two systems produced different dates there was generally a compromise so that both churches were able to celebrate on the same day. The process of working out the details generated still further controversies. The method from Alexandria became authoritative. In its developed form it was based on the epacts of a reckoned moon according to the 19 year Metonic cycle. Such a cycle was first proposed by Bishop Anatolius of Laodicea (in present-day Syria), c. 277.[a] Alexandrian Easter tables were composed by Pope Theophilus about 390 and within the bishopric of his nephew Cyril about 444. In Constantinople, several computists were active over the centuries after Anatolius (and after the Nicaean Council), but their Easter dates coincided with those of the Alexandrians. The Alexandrian computus was converted from the Alexandrian calendar into the Julian calendar in Rome by Dionysius Exiguus, though only for 95 years. Dionysius introduced the Christian Era (counting years from the Incarnation of Christ) when he published new Easter tables in 525.[15][16]

Dionysius's tables replaced earlier methods used by Rome. The earliest known Roman tables were devised in 222 by Hippolytus of Rome based on eight-year cycles. Then 84 year tables were introduced in Rome by Augustalis near the end of the 3rd century.[b] A completely distinct 84 year cycle, the Insular latercus, was used in the British Isles.[18] These old tables were used in Northumbria until 664, and by isolated monasteries as late as 931.[citation needed] A modified 84 year cycle was adopted in Rome during the first half of the 4th century. Victorius of Aquitaine tried to adapt the Alexandrian method to Roman rules in 457 in the form of a 532 year table, but he introduced serious errors.[19] These Victorian tables were used in Gaul (now France) and Spain until they were displaced by Dionysian tables at the end of the 8th century.

In the British Isles, Dionysius's and Victorius's tables conflicted with their traditional tables. These used an 84 year cycle because this made the dates of Easter repeat every 84 years – but an error made the full moons fall progressively too early.[18] Add the fact that Easter could fall, at earliest, on the fourteenth day of the lunar month and thus Queen Eanfled sometime during AD 662–664 – who followed the Dionysian system – fasted on her Palm Sunday on the same day as her husband Oswy, king of Northumbria, feasted on his Easter Sunday.[20]

As a result of the Irish Synod of Magh-Lene in 630, the southern Irish began to use the Dionysian tables,[21] and the northern English Synod of Whitby in 664 adopted the Dionysian tables.[22]Bede records that There happened an eclipse of the sun on the third of May, about ten o'clock in the morning.[23] The time is correct but the date is two days late.[c] This was done to conceal the inaccuracy that had accumulated in the new cycle since it was originally constructed.

The Dionysian reckoning was fully described by Bede in 725.[24] It may have been adopted by Charlemagne for the Frankish Church as early as 782 from Alcuin, a follower of Bede. The Dionysian/Bedan computus remained in use in western Europe until the Gregorian calendar reform, and remains in use in most Eastern Churches, including the vast majority of Eastern Orthodox Churches and Non-Chalcedonian Churches.[25] Having deviated from the Alexandrians during the 6th century, churches beyond the eastern frontier of the former Byzantine Empire, including the Assyrian Church of the East,[26] now celebrate Easter on different dates from Eastern Orthodox Churches four times every 532 years.[27]

Apart from these churches on the eastern fringes of the Roman empire, by the tenth century all had adopted the Alexandrian Easter, which still placed the vernal equinox on 21 March, although Bede had already noted its drift in 725 – it had drifted even further by the 16th century.[d] Worse, the reckoned Moon that was used to compute Easter was fixed to the Julian year by the 19 year cycle. That approximation built up an error of one day every 310 years, so by the 16th century the lunar calendar was out of phase with the real Moon by four days.

The Gregorian Easter has been used since 1583 by the Roman Catholic Church and was adopted by most Protestant churches between 1753 and 1845. German Protestant states used an astronomical Easter based on the Rudolphine Tables of Johannes Kepler between 1700 and 1774, while Sweden used it from 1739 to 1844. This astronomical Easter was one week before the Gregorian Easter in 1724, 1744, 1778, 1798, etc.[29]

Theory

| Year | Western | Eastern |

|---|---|---|

| 1999 | April 4 | April 11 |

| 2000 | April 23 | April 30 |

| 2001 | April 15 | |

| 2002 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2003 | April 20 | April 27 |

| 2004 | April 11 | |

| 2005 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2006 | April 16 | April 23 |

| 2007 | April 8 | |

| 2008 | March 23 | April 27 |

| 2009 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 2010 | April 4 | |

| 2011 | April 24 | |

| 2012 | April 8 | April 15 |

| 2013 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2014 | April 20 | |

| 2015 | April 5 | April 12 |

| 2016 | March 27 | May 1 |

| 2017 | April 16 | |

| 2018 | April 1 | April 8 |

| 2019 | April 21 | April 28 |

| 2020 | April 12 | April 19 |

| 2021 | April 4 | May 2 |

| 2022 | April 17 | April 24 |

| 2023 | April 9 | April 16 |

| 2024 | March 31 | May 5 |

| 2025 | April 20 | |

| 2026 | April 5 | April 12 |

| 2027 | March 28 | May 2 |

| 2028 | April 16 | |

| 2029 | April 1 | April 8 |

| 2030 | April 21 | April 28 |

| 2031 | April 13 | |

| 2032 | March 28 | May 2 |

| 2033 | April 17 | April 24 |

| 2034 | April 9 | |

| 2035 | March 25 | April 29 |

| 2036 | April 13 | April 20 |

| 2037 | April 5 | |

| 2038 | April 25 | |

| 2039 | April 10 | April 17 |

The Easter cycle groups days into lunar months, which are either 29 or 30 days long. There is an exception. The month ending in March normally has thirty days, but if 29 February of a leap year falls within it, it contains 31. As these groups are based on the lunar cycle, over the long term the average month in the lunar calendar is a very good approximation of the synodic month, which is 29.53059 days long.[30] There are 12 synodic months in a lunar year, totaling either 354 or 355 days. The lunar year is about 11 days shorter than the calendar year, which is either 365 or 366 days long. These days by which the solar year exceeds the lunar year are called epacts (Greek: ἐπακταὶ ἡμέραι, translit.epaktai hēmerai, lit. 'intercalary days').[31][32] It is necessary to add them to the day of the solar year to obtain the correct day in the lunar year. Whenever the epact reaches or exceeds 30, an extra intercalary month (or embolismic month) of 30 days must be inserted into the lunar calendar: then 30 must be subtracted from the epact. The Rev. C. Wheatly[33] provides the detail:

Thus beginning the year with March (for that was the ancient custom) they allowed thirty days for the moon [ending] in March, and twenty-nine for that [ending] in April; and thirty again for May, and twenty-nine for June &c. according to the old verses:

- Impar luna pari, par fiet in impare mense;

- In quo completur mensi lunatio detur.

'For the first, third, fifth, seventh, ninth, and eleventh months, which are called impares menses, or unequal months, have their moons according to computation of thirty days each, which are therefore called pares lunae, or equal moons: but the second, fourth, sixth, eighth, tenth, and twelfth months, which are called pares menses, or equal months, have their moons but twenty nine days each, which are called impares lunae, or unequal moons.

Thus the lunar month took the name of the Julian month in which it ended. The nineteen-year Metonic cycle assumes that 19 tropical years are as long as 235 synodic months. So after 19 years the lunations should fall the same way in the solar years, and the epacts should repeat. However, 19 × 11 = 209 ≡ 29 (mod 30), not 0 (mod 30); that is, 209 divided by 30 leaves a remainder of 29 instead of being a multiple of 30. So after 19 years, the epact must be corrected by one day for the cycle to repeat. This is the so-called saltus lunae ('leap of the moon'). The Julian calendar handles it by reducing the length of the lunar month that begins on 1 July in the last year of the cycle to 29 days. This makes three successive 29-day months.[e] The saltus and the seven extra 30-day months were largely hidden by being located at the points where the Julian and lunar months begin at about the same time. The extra months commenced on 3 December (year 2), 2 September (year 5), 6 March (year 8), 4 December (year 10), 2 November (year 13), 2 August (year 16), and 5 March (year 19).[34] The sequence number of the year in the 19-year cycle is called the 'golden number', and is given by the formula

- GN = Y mod 19 + 1

That is, the remainder of the year number Y in the Christian era when divided by 19, plus one.[f]

The paschal or Easter-month is the first one in the year to have its fourteenth day (its formal full moon) on or after 21 March. Easter is the Sunday after its 14th day (or, saying the same thing, the Sunday within its third week). The paschal lunar month always begins on a date in the 29-day period from 8 March to 5 April inclusive. Its fourteenth day, therefore, always falls on a date between 21 March and 18 April inclusive, and the following Sunday then necessarily falls on a date in the range 22 March to 25 April inclusive. In the solar calendar Easter is called a moveable feast since its date varies within a 35-day range. But in the lunar calendar, Easter is always the third Sunday in the paschal lunar month, and is no more 'moveable' than any holiday that is fixed to a particular day of the week and week within a month.

Tabular methods

Gregorian calendar

As reforming the computus was the primary motivation for the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1582, a corresponding computus methodology was introduced alongside the calendar.[g] The general method of working was given by Clavius in the Six Canons (1582), and a full explanation followed in his Explicatio (1603).

Easter Sunday is the Sunday following the paschal full moon date. The paschal full moon date is the ecclesiastical full moon date on or after 21 March. The Gregorian method derives paschal full moon dates by determining the epact for each year.[36] The epact can have a value from * (0 or 30) to 29 days. Theoretically a lunar month (epact 0) begins with the new moon, and the crescent moon is first visible on the first day of the month (epact 1).[37] The 14th day of the lunar month is considered the day of the full moon.[38]

Historically the paschal full moon date for a year was found from its sequence number in the Metonic cycle, called the golden number, which cycle repeats the lunar phase 1 January every 19 years.[39] This method was abandoned in the Gregorian reform because the tabular dates go out of sync with reality after about two centuries, but from the epact method, a simplified table can be constructed that has a validity of one to three centuries.[citation needed]

The epacts for the current Metonic cycle, which began in 2014, are:

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golden number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| Epact[40] | 29 | 10 | 21 | 2 | 13 | 24 | 5 | 16 | 27 | 8 | 19 | * | 11 | 22 | 3 | 14 | 25 | 6 | 17 |

| Paschal full moon date[41] | 14 April | 3 April | 23 March | 11 April | 31 March | 18 April | 8 April | 28 March | 16 April | 5 April | 25 March | 13 April | 2 April | 22 March | 10 April | 30 March | 17 April | 7 April | 27 March |

The above table is valid from 1900 to 2199 inclusive. As an example of use, the golden number for 2038 is 6 (2038 ÷ 19 = 107 remainder 5, then +1 = 6). From the table, paschal full moon for golden number 6 is 18 April. From week table 18 April is Sunday. Easter Sunday is the following Sunday, 25 April.

The epacts are used to find the dates of the new moon in the following way: Write down a table of all 365 days of the year (the leap day is ignored). Then label all dates with a Roman numeral counting downwards, from '*' (0 or 30), 'xxix' (29), down to 'i' (1), starting from 1 January, and repeat this to the end of the year. However, in every second such period count only 29 days and label the date with xxv (25) also with xxiv (24). Treat the 13th period (last eleven days) as long, therefore, and assign the labels 'xxv' and 'xxiv' to sequential dates (26 and 27 December respectively). Finally, in addition, add the label '25' to the dates that have 'xxv' in the 30-day periods; but in 29-day periods (which have 'xxiv' together with 'xxv') add the label '25' to the date with 'xxvi'. The distribution of the lengths of the months and the length of the epact cycles is such that each civil calendar month starts and ends with the same epact label, except for February and for the epact labels 'xxv' and '25' in July and August. This table is called the calendarium. The ecclesiastical new moons for any year are those dates when the epact for the year is entered. If the epact for the year is for instance 27, then there is an ecclesiastical new moon on every date in that year that has the epact label 'xxvii' (27).

Also label all the dates in the table with letters 'A' to 'G', starting from 1 January, and repeat to the end of the year. If, for instance, the first Sunday of the year is on 5 January, which has letter 'E', then every date with the letter 'E' is a Sunday that year. Then 'E' is called the dominical letter for that year (from Latin: dies domini, day of the Lord). The dominical letter cycles backward one position every year. However, in leap years after 24 February the Sundays fall on the previous letter of the cycle, so leap years have two dominical letters: the first for before, the second for after the leap day.

In practice, for the purpose of calculating Easter, this need not be done for all 365 days of the year. For the epacts, March comes out exactly the same as January, so one need not calculate January or February. To also avoid the need to calculate the Dominical Letters for January and February, start with D for 1 March. You need the epacts only from 8 March to 5 April. This gives rise to the following table:

| Label | March | DL | April | DL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | 1 | D | ||

| xxix | 2 | E | 1 | G |

| xxviii | 3 | F | 2 | A |

| xxvii | 4 | G | 3 | B |

| xxvi | 5 | A | 4 | C |

| 25 | 6 | B | ||

| xxv | 5 | D | ||

| xxiv | 7 | C | ||

| xxiii | 8 | D | 6 | E |

| xxii | 9 | E | 7 | F |

| xxi | 10 | F | 8 | G |

| xx | 11 | G | 9 | A |

| xix | 12 | A | 10 | B |

| xviii | 13 | B | 11 | C |

| xvii | 14 | C | 12 | D |

| xvi | 15 | D | 13 | E |

| xv | 16 | E | 14 | F |

| xiv | 17 | F | 15 | G |

| xiii | 18 | G | 16 | A |

| xii | 19 | A | 17 | B |

| xi | 20 | B | 18 | C |

| x | 21 | C | 19 | D |

| ix | 22 | D | 20 | E |

| viii | 23 | E | 21 | F |

| vii | 24 | F | 22 | G |

| vi | 25 | G | 23 | A |

| v | 26 | A | 24 | B |

| iv | 27 | B | 25 | C |

| iii | 28 | C | 26 | D |

| ii | 29 | D | 27 | E |

| i | 30 | E | 28 | F |

| * | 31 | F | 29 | G |

| xxix | 30 | A |

Example: If the epact is 27 (xxvii), an ecclesiastical new moon falls on every date labeled xxvii. The ecclesiastical full moon falls 13 days later. From the table above, this gives a new moon on 4 March and 3 April, and so a full moon on 17 March and 16 April.

Then Easter Day is the first Sunday after the first ecclesiastical full moon on or after 21 March. This definition uses 'on or after 21 March' to avoid ambiguity with historic meaning of the word 'after'. In modern language, this phrase simply means 'after 20 March'. The definition of 'on or after 21 March' is frequently incorrectly abbreviated to 'after 21 March' in published and web-based articles, resulting in incorrect Easter dates.

In the example, this paschal full moon is on 16 April. If the dominical letter is E, then Easter day is on 20 April.

The label '25' (as distinct from 'xxv') is used as follows: Within a Metonic cycle, years that are 11 years apart have epacts that differ by one day. A month beginning on a date having labels xxiv and xxv impacted together has either 29 or 30 days. If the epacts 24 and 25 both occur within one Metonic cycle, then the new (and full) moons would fall on the same dates for these two years. This is possible for the real moon[h] but is inelegant in a schematic lunar calendar; the dates should repeat only after 19 years. To avoid this, in years that have epacts 25 and with a Golden Number larger than 11, the reckoned new moon falls on the date with the label 25 rather than xxv. Where the labels 25 and xxv are together, there is no problem since they are the same. This does not move the problem to the pair '25' and 'xxvi', because the earliest epact 26 could appear would be in year 23 of the cycle, which lasts only 19 years: there is a saltus lunae in between that makes the new moons fall on separate dates.

The Gregorian calendar has a correction to the tropical year by dropping three leap days in 400 years (always in a century year). This is a correction to the length of the tropical year, but should have no effect on the Metonic relation between years and lunations. Therefore, the epact is compensated for this (partially – see epact) by subtracting one in these century years. This is the so-called solar correction or 'solar equation' ('equation' being used in its medieval sense of 'correction').

However, 19 uncorrected Julian years are a little longer than 235 lunations. The difference accumulates to one day in about 310 years. Therefore, in the Gregorian calendar, the epact gets corrected by adding 1 eight times in 2,500 (Gregorian) years, always in a century year: this is the so-called lunar correction (historically called 'lunar equation'). The first one was applied in 1800, the next is in 2100, and will be applied every 300 years except for an interval of 400 years between 3900 and 4300, which starts a new cycle.

The solar and lunar corrections work in opposite directions, and in some century years (for example, 1800 and 2100) they cancel each other. The result is that the Gregorian lunar calendar uses an epact table that is valid for a period of from 100 to 300 years. The epact table listed above is valid for the period 1900 to 2199.

Details

This method of computation has several subtleties:

Every other lunar month has only 29 days, so one day must have two (of the 30) epact labels assigned to it. The reason for moving around the epact label 'xxv/25' rather than any other seems to be the following: According to Dionysius (in his introductory letter to Petronius), the Nicene council, on the authority of Eusebius, established that the first month of the ecclesiastical lunar year (the paschal month) should start between 8 March and 5 April inclusive, and the 14th day fall between 21 March and 18 April inclusive, thus spanning a period of (only) 29 days. A new moon on 7 March, which has epact label 'xxiv', has its 14th day (full moon) on 20 March, which is too early (not following 20 March). So years with an epact of 'xxiv', if the lunar month beginning on 7 March had 30 days, would have their paschal new moon on 6 April, which is too late: The full moon would fall on 19 April, and Easter could be as late as 26 April. In the Julian calendar the latest date of Easter was 25 April, and the Gregorian reform maintained that limit. So the paschal full moon must fall no later than 18 April and the new moon on 5 April, which has epact label 'xxv'. 5 April must therefore have its double epact labels 'xxiv' and 'xxv'. Then epact 'xxv' must be treated differently, as explained in the paragraph above.

As a consequence, 19 April is the date on which Easter falls most frequently in the Gregorian calendar: In about 3.87% of the years. 22 March is the least frequent, with 0.48%.

The relation between lunar and solar calendar dates is made independent of the leap day scheme for the solar year. Basically the Gregorian calendar still uses the Julian calendar with a leap day every four years, so a Metonic cycle of 19 years has 6,940 or 6,939 days with five or four leap days. Now the lunar cycle counts only 19 × 354 + 19 × 11 = 6,935 days. By not labeling and counting the leap day with an epact number, but having the next new moon fall on the same calendar date as without the leap day, the current lunation gets extended by a day,[i] and the 235 lunations cover as many days as the 19 years. So the burden of synchronizing the calendar with the moon (intermediate-term accuracy) is shifted to the solar calendar, which may use any suitable intercalation scheme; all under the assumption that 19 solar years = 235 lunations (long-term inaccuracy). A consequence is that the reckoned age of the moon may be off by a day, and also that the lunations that contain the leap day may be 31 days long, which would never happen if the real moon were followed (short-term inaccuracies). This is the price for a regular fit to the solar calendar.

From the perspective of those who might wish to use the Gregorian Easter cycle as a calendar for the entire year, there are some flaws in the Gregorian lunar calendar[43] (although they have no effect on the paschal month and the date of Easter):

- Lunations of 31 (and sometimes 28) days occur.

- If a year with Golden Number 19 happens to have epact 19, then the last ecclesiastical new moon falls on 2 December; the next would be due on 1 January. However, at the start of the new year, a saltus lunae increases the epact by another unit, and the new moon should have occurred on the previous day. So a new moon is missed. The calendarium of the Missale Romanum takes account of this by assigning epact label '19' instead of 'xx' to 31 December of such a year, making that date the new moon. It happened every 19 years when the original Gregorian epact table was in effect (for the last time in 1690), and next happens in 8511.

- If the epact of a year is 20, an ecclesiastical new moon falls on 31 December. If that year falls before a century year, then in most cases, a solar correction reduces the epact for the new year by one: The resulting epact '*' means that another ecclesiastical new moon is counted on 1 January. So, formally, a lunation of one day has passed. This next happens in 4199–4200.

- Other borderline cases occur (much) later, and if the rules are followed strictly and these cases are not specially treated, they generate successive new moon dates that are 1, 28, 59, or (very rarely) 58 days apart.

A careful analysis shows that through the way they are used and corrected in the Gregorian calendar, the epacts are actually fractions of a lunation (1/30, also known as a tithi) and not full days. See epact for a discussion.

The solar and lunar corrections repeat after 4 × 25 = 100 centuries. In that period, the epact has changed by a total of −1 × 3/4 × 100 + 1 × 8/25 × 100 = −43 ≡ 17 mod 30. This is prime to the 30 possible epacts, so it takes 100 × 30 = 3,000 centuries before the epacts repeat; and 3,000 × 19 = 57,000 centuries before the epacts repeat at the same golden number. This period has 5,700,000/19 × 235 − 43/30 × 57,000/100 = 70,499,183 lunations. So the Gregorian Easter dates repeat in exactly the same order only after 5,700,000 years, 70,499,183 lunations, or 2,081,882,250 days; the mean lunation length is then 29.53058690 days. However, the calendar must already have been adjusted after some millennia because of changes in the length of the tropical year, the synodic month, and the day.

This raises the question why the Gregorian lunar calendar has separate solar and lunar corrections, which sometimes cancel each other. Instead, the net 4 × 8 − 3 × 25 = 43 epact subtractions could be distributed evenly over 10,000 years (as has been proposed for example by Dr. Heiner Lichtenberg).[44] Lilius' original work has not been preserved and Clavius does not explain this. However Lilius did say that the correction system he devised was to be a perfectly flexible tool in the hands of future calendar reformers, since the solar and lunar calendar could henceforth be corrected without mutual interference.[45] If the corrections are combined, then the inaccuracies of the two cycles are also added and can not be corrected separately.

The 'solar corrections' approximately undo the effect of the Gregorian modifications to the leap days of the solar calendar on the lunar calendar: they (partially) bring the epact cycle back to the original Metonic relation between the Julian year and lunar month. The inherent mismatch between sun and moon in this basic 19 year cycle is then corrected every three or four centuries by the 'lunar correction' to the epacts. However, the epact corrections occur at the beginning of Gregorian centuries, not Julian centuries, and therefore the original Julian Metonic cycle is not fully restored.

The ratios of (mean solar) days per year and days per lunation change both because of intrinsic long-term variations in the orbits, and because the rotation of the Earth is slowing down due to tidal deceleration, so the Gregorian parameters become increasingly obsolete.

This does affect the date of the equinox, but it so happens that the interval between northward (northern hemisphere spring) equinoxes has been fairly stable over historical times, especially if measured in mean solar time (see,[46] esp.[47])

Also the drift in ecclesiastical full moons calculated by the Gregorian method compared to the true full moons is affected less than one would expect, because the increase in the length of the day is almost exactly compensated for by the increase in the length of the month, as tidal braking transfers angular momentum of the rotation of the Earth to orbital angular momentum of the Moon.

The Ptolemaic value of the length of the mean synodic month, established around the 4th century BCE by the Babylonians, is 29 days 12 hr 44 min 31/3 s (see Kidinnu); the current value is 0.46 s less (see New moon). In the same historic stretch of time the length of the mean tropical year has diminished by about 10 s (all values mean solar time).

British Calendar Act and Book of Common Prayer

The portion of the Tabular methods section above describes the historical arguments and methods by which the present dates of Easter Sunday were decided in the late 16th century by the Catholic Church. In Britain, where the Julian calendar was then still in use, Easter Sunday was defined, from 1662 to 1752 (in accordance with previous practice), by a simple table of dates in the AnglicanPrayer Book (decreed by the Act of Uniformity 1662). The table was indexed directly by the golden number and the Sunday letter, which (in the Easter section of the book) were presumed to be already known.

For the British Empire and colonies, the new determination of the Date of Easter Sunday was defined by what is now called the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 with its Annexe. The method was chosen to give dates agreeing with the Gregorian rule already in use elsewhere. The Act required that it be put in the Book of Common Prayer, and therefore it is the general Anglican rule. The original Act can be seen in the British Statutes at Large 1765.[48] The Annexe to the Act includes the definition: 'Easter-day (on which the rest depend) is always the first Sunday after the Full Moon, which happens upon, or next after the Twenty-first Day of March. And if the Full Moon happens upon a Sunday, Easter-day is the Sunday after.' The Annexe subsequently uses the terms 'Paschal Full Moon' and 'Ecclesiastical Full Moon', making it clear that they approximate to the real full moon.

The method is quite distinct from that described above in Gregorian calendar. For a general year, one first determines the golden number, then one uses three tables to determine the Sunday letter, a 'cypher', and the date of the paschal full moon, from which the date of Easter Sunday follows. The epact does not explicitly appear. Simpler tables can be used for limited periods (such as 1900–2199) during which the cypher (which represents the effect of the solar and lunar corrections) does not change. Clavius' details were employed in the construction of the method, but they play no subsequent part in its use.[49][50]

J. R. Stockton shows his derivation of an efficient computer algorithm traceable to the tables in the Prayer Book and the Calendar Act (assuming that a description of how to use the Tables is at hand), and verifies its processes by computing matching Tables.[51]

Julian calendar

The method for computing the date of the ecclesiastical full moon that was standard for the western Church before the Gregorian calendar reform, and is still used today by most eastern Christians, made use of an uncorrected repetition of the 19-year Metonic cycle in combination with the Julian calendar. In terms of the method of the epacts discussed above, it effectively used a single epact table starting with an epact of 0, which was never corrected. In this case, the epact was counted on 22 March, the earliest acceptable date for Easter. This repeats every 19 years, so there are only 19 possible dates for the paschal full moon from 21 March to 18 April inclusive.

Because there are no corrections as there are for the Gregorian calendar, the ecclesiastical full moon drifts away from the true full moon by more than three days every millennium. It is already a few days later. As a result, the eastern churches celebrate Easter one week later than the western churches about 50% of the time. (The eastern Easter is often four or five weeks later because the Julian calendar is 13 days behind the Gregorian in 1900–2099, and so the Gregorian paschal full moon is often before Julian 21 March.)

The sequence number of a year in the 19-year cycle is called its golden number. This term was first used in the computistic poem Massa Compoti by Alexander de Villa Dei in 1200. A later scribe added the golden number to tables originally composed by Abbo of Fleury in 988.

The claim by the Catholic Church in the 1582 papal bullInter gravissimas, which promulgated the Gregorian calendar, that it restored 'the celebration of Easter according to the rules fixed by .. the great ecumenical council of Nicaea'[52] was based on a false claim by Dionysius Exiguus (525) that 'we determine the date of Easter Day .. in accordance with the proposal agreed upon by the 318 Fathers of the Church at the Council in Nicaea.'[53] The First Council of Nicaea (325) only stated that all Christians must celebrate Easter on the same Sunday—it did not fix rules to determine which Sunday. The medieval computus was based on the Alexandrian computus, which was developed by the Church of Alexandria during the first decade of the 4th century using the Alexandrian calendar.[54]:36 The eastern Roman Empire accepted it shortly after 380 after converting the computus to the Julian calendar.[54]:48 Rome accepted it sometime between the sixth and ninth centuries. The British Isles accepted it during the eighth century except for a few monasteries. Francia (all of western Europe except Scandinavia (pagan), the British Isles, the Iberian peninsula, and southern Italy) accepted it during the last quarter of the eighth century. The last Celtic monastery to accept it, Iona, did so in 716, whereas the last English monastery to accept it did so in 931. Before these dates, other methods produced Easter Sunday dates that could differ by up to five weeks.

This is the table of paschal full moon dates for all Julian years since 931:

| Golden number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paschal full moon date | 5 April | 25 March | 13 April | 2 April | 22 March | 10 April | 30 March | 18 April | 7 April | 27 March | 15 April | 4 April | 24 March | 12 April | 1 April | 21 March | 9 April | 29 March | 17 April |

Example calculation using this table:

The golden number for 1573 is 16 (1573 + 1 = 1574; 1574 ÷ 19 = 82 remainder 16). From the table, the paschal full moon for golden number 16 is 21 March. From the week table 21 March is Saturday. Easter Sunday is the following Sunday, 22 March.

So for a given date of the ecclesiastical full moon, there are seven possible Easter dates. The cycle of Sunday letters, however, does not repeat in seven years: because of the interruptions of the leap day every four years, the full cycle in which weekdays recur in the calendar in the same way, is 4 × 7 = 28 years, the so-called solar cycle. So the Easter dates repeated in the same order after 4 × 7 × 19 = 532 years. This paschal cycle is also called the Victorian cycle, after Victorius of Aquitaine, who introduced it in Rome in 457. It is first known to have been used by Annianus of Alexandria at the beginning of the 5th century. It has also sometimes erroneously been called the Dionysian cycle, after Dionysius Exiguus, who prepared Easter tables that started in 532; but he apparently did not realize that the Alexandrian computus he described had a 532-year cycle, although he did realize that his 95-year table was not a true cycle. Venerable Bede (7th century) seems to have been the first to identify the solar cycle and explain the paschal cycle from the Metonic cycle and the solar cycle.

In medieval western Europe, the dates of the paschal full moon (14 Nisan) given above could be memorized with the help of a 19-line alliterative poem in Latin:[55][56]

| Nonae Aprilis | norunt quinos | V |

| octonae kalendae | assim depromunt. | I |

| Idus Aprilis | etiam sexis, | VI |

| nonae quaternae | namque dipondio. | II |

| Item undene | ambiunt quinos, | V |

| quatuor idus | capiunt ternos. | III |

| Ternas kalendas | titulant seni, | VI |

| quatuor dene | cubant in quadris. | IIII |

| Septenas idus | septem eligunt, | VII |

| senae kalendae | sortiunt ternos, | III |

| denis septenis | donant assim. | I |

| Pridie nonas | porro quaternis, | IIII |

| nonae kalendae | notantur septenis. | VII |

| Pridie idus | panditur quinis, | V |

| kalendas Aprilis | exprimunt unus. | I |

| Duodene namque | docte quaternis, | IIII |

| speciem quintam | speramus duobus. | II |

| Quaternae kalendae | quinque coniciunt, | V |

| quindene constant | tribus adeptis. | III |

The first half-line of each line gives the date of the paschal full moon from the table above for each year in the 19-year cycle. The second half-line gives the ferial regular, or weekday displacement, of the day of that year's paschal full moon from the concurrent, or the weekday of 24 March.[57] The ferial regular is repeated in Roman numerals in the third column.

Algorithms

Note on operations

When expressing Easter algorithms without using tables, it has been customary to employ only the integer operations addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, modulo, and assignment (plus minus times div mod assign). That is compatible with the use of simple mechanical or electronic calculators. But it is an undesirable restriction for computer programming, where conditional operators and statements, as well as look-up tables, are always available. One can easily see how conversion from day-of-March (22 to 56) to day-and-month (22 March to 25 April) can be done as (if DoM>31) {Day=DoM-31, Month=Apr} else {Day=DoM, Month=Mar}. More importantly, using such conditionals also simplifies the core of the Gregorian calculation.

Gauss's Easter algorithm

In 1800, the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss presented this algorithm for calculating the date of the Julian or Gregorian Easter.[58][59] He corrected the expression for calculating the variable p in 1816.[60] In 1800 he incorrectly stated p = floor (k/3) = ⌊k/3⌋. In 1807 he replaced the condition (11M + 11) mod 30 < 19 with the simpler a > 10. In 1811 he limited his algorithm to the 18th and 19th centuries only, and stated that 26 April is always replaced with 19 April and 25 April by 18 April. In 1816 he thanked his student Peter Paul Tittel for pointing out that p was wrong in the original version.[61]

| Expression | year = 1777 |

|---|---|

| a = year mod 19 | a = 10 |

| b = year mod 4 | b = 1 |

| c = year mod 7 | c = 6 |

| k = ⌊year/100⌋ | k = 17 |

| p = ⌊13 + 8k/25⌋ | p = 5 |

| q = ⌊k/4⌋ | q = 4 |

| M = (15 − p + k − q) mod 30 | M = 23 |

| N = (4 + k − q) mod 7 | N = 3 |

| d = (19a + M) mod 30 | d = 3 |

| e = (2b + 4c + 6d + N) mod 7 | e = 5 |

| Gregorian Easter is 22 + d + e March or d + e − 9 April | 30 March |

| if d = 29 and e = 6, replace 26 April with 19 April | |

| if d = 28, e = 6, and (11M + 11) mod 30 < 19, replace 25 April with 18 April | |

| For the Julian Easter in the Julian calendar M = 15 and N = 6 (k, p, and q are unnecessary) | |

An analysis of the Gauss's Easter algorithm is divided into two parts. The first part is the approximate tracking of the lunar orbiting and the second one is the exact, deterministic offsetting to obtain a Sunday following the full moon.

The first part consists of determining the variable d, the number of days (counting from March 21) for the closest following full moon to occur. The formula for d contains the terms 19a and the constant M. a is the year's position in the 19-year lunar phase cycle, in which by assumption the moon's movement relative to earth repeats every 19 calendar years. In older times, 19 calendar years were equated to 235 lunar months (the Metonic cycle), which is remarkably close since 235 lunar months are approximately 6939.6813 days and 19 years are on average 6939.6075 days. The expression (19a + M) mod 30 repeats every 19 years within each century as M is determined per century. The 19-year cycle has nothing to do with the '19' in 19a, it is just a coincidence that another '19' appears. The '19' in 19a comes from correcting the mismatch between a calendar year and an integer number of lunar months. A calendar year (non-leap year) has 365 days and the closest you can come with an integer number of lunar months is 12 × 29.5 = 354 days. The difference is 11 days, which must be corrected for by moving the following year's occurrence of a full moon 11 days back. But in modulo 30 arithmetic, subtracting 11 is the same as adding 19, hence the addition of 19 for each year added, i.e. 19a.

The M in 19a + M serves to have a correct starting point at the start of each century. It is determined by a calculation taking the number of leap years up until that century where k inhibits a leap day every 100 years and q reinstalls it every 400 years, yielding (k − q) as the total number of inhibitions to the pattern of a leap day every four years. Thus we add (k − q) to correct for leap days that never occurred. p corrects for the lunar orbit not being fully describable in integer terms.

The range of days considered for the full moon to determine Easter are 21 March (the day of the ecclesislastical equinox of spring) to 19 April—a 30-day range mirrored in the mod 30 arithmetic of variable d and constant M, both of which can have integer values in the range 0 to 29. Once d is determined, this is the number of days to add to 21 March (the earliest possible full moon allowed, which is coincident with the ecclesiastical equinox of spring) to obtain the day of the full moon.

So the first allowable date of Easter is 21+d+1, as Easter is to celebrate the Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon, that is if the full moon falls on Sunday 21 March Easter is to be celebrated 7 days after, while if the full moon falls on Saturday 21 March Easter is the following 22 March.

The second part is finding e, the additional offset days that must be added to the date offset d to make it arrive at a Sunday. Since the week has 7 days, the offset must be in the range 0 to 6 and determined by modulo 7 arithmetic. e is determined by calculating 2b + 4c + 6d + N mod 7. These constants may seem strange at first, but are quite easily explainable if we remember that we operate under mod 7 arithmetic. To begin with, 2b + 4c ensures that we take care of the fact that weekdays slide for each year. A normal year has 365 days, but 52 × 7 = 364, so 52 full weeks make up one day too little. Hence, each consecutive year, the weekday 'slides one day forward', meaning if May 6 was a Wednesday one year, it is a Thursday the following year (disregarding leap years). Both b and c increases by one for an advancement of one year (disregarding modulo effects). The expression 2b + 4c thus increases by 6—but remember that this is the same as subtracting 1 mod 7. And to subtract by 1 is exactly what is required for a normal year – since the weekday slips one day forward we should compensate one day less to arrive at the correct weekday (i.e. Sunday). For a leap year, b becomes 0 and 2b thus is 0 instead of 8—which under mod 7, is another subtraction by 1—i.e., a total subtraction by 2, as the weekdays after the leap day that year slides forward by two days.

The expression 6d works the same way. Increasing d by some number y indicates that the full moon occurs y days later this year, and hence we should compensate y days less. Adding 6d is mod 7 the same as subtracting d, which is the desired operation. Thus, again, we do subtraction by adding under modulo arithmetic. In total, the variable e contains the step from the day of the full moon to the nearest following Sunday, between 0 and 6 days ahead. The constant N provides the starting point for the calculations for each century and depends on where Jan 1, year 1 was implicitly located when the Gregorian calendar was constructed.

The expression d + e can yield offsets in the range 0 to 35 pointing to possible Easter Sundays on March 22 to April 26. For reasons of historical compatibility, all offsets of 35 and some of 34 are subtracted by 7, jumping one Sunday back to the day before the full moon (in effect using a negative e of −1). This means that 26 April is never Easter Sunday and that 19 April is overrepresented. These latter corrections are for historical reasons only and has nothing to do with the mathematical algorithm.

Using the Gauss's Easter algorithm for years prior to 1583 is historically pointless since the Gregorian calendar was not utilised for determining Easter before that year. Using the algorithm far into the future is questionable, since we know nothing about how different churches will define Easter that far ahead. Easter calculations are based on agreements and conventions, not on the actual celestial movements nor on indisputable facts of history.

Anonymous Gregorian algorithm

'A New York correspondent' submitted this algorithm for determining the Gregorian Easter to the journal Nature in 1876.[61][62]It has been reprinted many times, e.g.,in 1877 by Samuel Butcher in The Ecclesiastical Calendar,[63]:225 in 1916 by Arthur Downing in The Observatory,[64]in 1922 by H. Spencer Jones in General Astronomy,[65]in 1977 by the Journal of the British Astronomical Association,[66]in 1977 by The Old Farmer's Almanac,in 1988 by Peter Duffett-Smith in Practical Astronomy with your Calculator,and in 1991 by Jean Meeus in Astronomical Algorithms.[67]Because of the Meeus’ book citation, that is also called 'Meeus/Jones/Butcher' algorithm:

| Expression | Y = 1961 | Y = 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| a = Y mod 19 | a = 4 | a = 5 |

| b = Y div 100 | b = 19 | b = 20 |

| c = Y mod 100 | c = 61 | c = 19 |

| d = b div 4 | d = 4 | d = 5 |

| e = b mod 4 | e = 3 | e = 0 |

| f = (b + 8) div 25 | f = 1 | f = 1 |

| g = (b − f + 1) div 3 | g = 6 | g = 6 |

| h = (19a + b − d − g + 15) mod 30 | h = 10 | h = 29 |

| i = c div 4 | i = 15 | i = 4 |

| k = c mod 4 | k = 1 | k = 3 |

| ℓ = (32 + 2e + 2i − h − k) mod 7 | ℓ = 1 | ℓ = 1 |

| m = (a + 11h + 22ℓ) div 451 | m = 0 | m = 0 |

| month = (h + ℓ − 7m + 114) div 31 | month = 4 (April) | month = 4 (April) |

| day = ((h + ℓ − 7m + 114) mod 31) + 1 | day = 2 | day = 21 |

| Gregorian Easter | 2 April 1961 | 21 April 2019 |

In 1961 the New Scientist published a version of the Nature algorithm incorporating a few changes.[68] The variable g was calculated using Gauss' 1816 correction, resulting in the elimination of variable f. Some tidying results in the replacement of variable o (to which one must be added to obtain the date of Easter) with variable p, which gives the date directly.

Meeus's Julian algorithm

Jean Meeus, in his book Astronomical Algorithms (1991, p. 69), presents the following algorithm for calculating the Julian Easter on the Julian Calendar, which is not the Gregorian Calendar used throughout the contemporary world. To obtain the date of Eastern Orthodox Easter on the latter calendar, 13 days (as of 1900 through 2099) must be added to the Julian dates, producing the dates below, in the last row.

| Expression | Y = 2008 | Y = 2009 | Y = 2010 | Y = 2011 | Y = 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a = Y mod 4 | a = 0 | a = 1 | a = 2 | a = 3 | a = 0 |

| b = Y mod 7 | b = 6 | b = 0 | b = 1 | b = 2 | b = 0 |

| c = Y mod 19 | c = 13 | c = 14 | c = 15 | c = 16 | c = 2 |

| d = (19c + 15) mod 30 | d = 22 | d = 11 | d = 0 | d = 19 | d = 23 |

| e = (2a + 4b − d + 34) mod 7 | e = 1 | e = 4 | e = 0 | e = 1 | e = 4 |

| month = (d + e + 114) div 31 | 4 (April) | 4 (April) | 3 (March) | 4 (April) | 4 (April) |

| day = ((d + e + 114) mod 31) + 1 | 14 | 6 | 22 | 11 | 18 |

| Easter Day (Julian calendar) | 14 April 2008 | 6 April 2009 | 22 March 2010 | 11 April 2011 | 18 April 2016 |

| Easter Day (Gregorian calendar) | 27 April 2008 | 19 April 2009 | 4 April 2010 | 24 April 2011 | 1 May 2016 |

See also

Notes

- ^The lunar cycle of Anatolius, according to the tables in De ratione paschali, included only two bissextile (leap) years every 19 years, so could not be used by anyone using the Julian calendar, which had four or five leap years per lunar cycle.[13][14]

- ^Although this is the dating of Augustalis by Bruno Krusch, see arguments for a 5th century date in[17]

- ^In that year, the Golden Number being 19, the ecclesiastical full moon (luna xiv) fell on 17 April. The Easter month has 29 days, so the next new moon fell sixteen days later, on 3 May.

- ^For example, in the Julian calendar, at Rome in 1550, the March equinox occurred at 11 March 6:51 AM local mean time.[28]

- ^Although prior to the replacement of the Julian calendar in 1752 some printers of the Book of Common Prayer placed the saltus correctly, beginning the next month on 30 July, none of them continued the sequence correctly to the end of the year.

- ^'the [Golden Number] of a year AD is found by adding one, dividing by 19, and taking the remainder (treating 0 as 19).' [35]

- ^See especially the first,second,fourth, andsixth canon, and thecalendarium

- ^In 2004 and again in 2015 there are full moons on 2 July and 31 July

- ^Traditionally in the Christian West, this situation was handled by extending the first 29 day lunar month of the year to 30 days, and beginning the following lunar month one day later than otherwise if it was due to begin before the leap day.[42]

Sources

- ^Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008), The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era, Oxford Early Christian Studies, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 40, ISBN978-0-19-954312-0

- ^Caroline Wyatt (25 March 2016). 'Why can't the date of Easter be fixed'. BBC. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^'NPNF2-01. Eusebius Pamphilius: Church History, Life of Constantine, Oration in Praise of Constantine'. Ccel.org. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^Schwartz, E. (1905). Christliche und jüdische Ostertafeln. Berlin, DE. pp. 104 ff.

- ^Gibson, Margaret Dunlop (1903). The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac. London, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 100.

- ^Peter of Alexandria, quoted in the preface to the Chronicon Paschale, Migne, PG 18, 512.

- ^Stern, Sacha (2001). Calendar and Community: A history of the Jewish calendar second century BCE – tenth century CE. Oxford University Press. p. 72–79.

- ^Epiphanius. Adversus Haereses. 3.1.10. quotes a version of the Apostolic Constitutions used by the sect of the Audiani, which advises Christians not to do their own calculation, but to use the Jewish computation even if the Jewish computation is in error.

- ^Emperor Constantine. 'On the keeping of Easter (from the letter of the Emperor to all those not present at the Council, found in Eusebius, Vita Const., Lib. iii., 18-20'. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^Hefele, Charles Joseph (1883). A History of the Christian Councils. Translated by Clark, William R. pp. 322–325.

ιδʹ is the Greek number 14, short for 14 Nisan

- ^Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008). The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era. Oxford Early Christian Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN978-0-19-954312-0.

- ^Pedersen, Olaf (1983). 'The Ecclesiastical Calendar and the Life of the Church'. In Coyne, G V; Hoskin, M A; Pedersen, O (eds.). Gregorian Reform of the Calendar: Proceedings of the Vatican conference to commemorate its 400th anniversary 1582-1989. Vatican City. pp. 42–43.

- ^Turner, C.H. (1895). 'The Paschal Canon of Anatolius of Laodicea'. The English Historical Review. 10: 699–710.

- ^McCarthy, Daniel (1995–1996). 'The Lunar and Paschal Tables of De ratione paschali Attributed to Anatolius of Laodicea'. Archive for History of Exact Sciences. 49: 285–320.

- ^Audette, Rodolphe. 'Dionysius Exiguus - Liber de Paschate'. henk-reints.nl. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^For confirmation of Dionysius's role see Blackburn & Holford-Strevens p. 794.

- ^Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008). The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era. Oxford University Press. pp. 217, 227–228. ISBN978-0-19-954312-0.

- ^ abMcCarthy, Daniel (August 1993). 'Easter principles and a fifth-century lunar cycle used in the British Isles'. Journal for the History of Astronomy. 24(3) (76): 204–224. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- ^Blackburn & Holford-Strevens p. 793.

- ^Bede (1907) [731], Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England, translated by Sellar, A. M.; Giles, J. A., Project Gutenberg, Book III, Chapter XXV,

.. when the king, having ended his fast, was keeping Easter, the queen and her followers were still fasting, and celebrating Palm Sunday.

- ^Jones, Charles W. (1943), 'Development of the Latin Ecclesiastical Calendar', Bedae Opera de Temporibus, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Mediaeval Academy of America, p. 90,

The letter [of Cummian] is at once a report and an apology or justification to Abbot Seghine at Iona of a synod held at Campus Lenis (Magh-Lene), where the Easter question was considered. The direct result of the synod was an alteration in the observance among the southern Irish and the adoption of the Alexandrian reckoning.

- ^Bede. Ecclesiastical History of England. Book III, Chapter XXV.

- ^Bede. Ecclesiastical History of England. Book III, Chapter XXVII.

There happened an eclipse of the sun on the third of May, about ten o'clock in the morning.

- ^Bede (1999). Wallis, Faith (ed.). Bede: The Reckoning of Time. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press. pp. lix–lxiii.

- ^Kekis, Theoharis. 'The Orthodox Church Calendar'(PDF). Cyprus Action Network of America.

- ^'The Many Easters & Eosters for the Many: A Choice of Hallelujahs'. Revradiotowerofsong.org. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^'Loading'. Knowledgeonfingertips.com. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^'Seasons calculator'. Time and Date AS. 2014.

- ^Lamont, Roscoe (1920). 'The reform of the Julian calendar'. Popular Astronomy. Vol. 28. pp. 18–31.

- ^Richards, 2013, p. 587. The day consists of 86,400 SI seconds, and the same value is given for the years 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000.

- ^ἐπακτός. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^Harper, Douglas. 'epact'. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^Rev C Wheatly, A Rational Illustration of the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England, Oxford 1794, p. 42.

- ^Bede (tr. Faith Wallis) (1999). The Reckoning of Time. Liverpool. p. xlvi. ISBN978-0-85323-693-1.

- ^Blackburn & Holford-Strevens p. 810.

- ^Dershowitz & Reingold, 2008, pp. 113–117

- ^Mosshammer, 2008, p. 76: 'Theoretically, the epact 30=0 represents the new moon at its conjunction with the sun. The epact of 1 represents the theoretical first visibility of the first crescent of the moon. It is from that point as day one that the fourteenth day of the moon is counted.'

- ^Dershowitz & Reingold, 2008, pp. 114–115

- ^Dershowitz & Reingold, 2008, p. 114

- ^Can be verified by using Blackburn and Holford-Strevens, Table 7, p. 825

- ^Weisstein (c. 2006) 'Paschal full moon' agrees with this line of table through 2009.

- ^Blackburn, Bonnie; Holford-Stevens, Leofranc (1999). The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford University Press. p. 813.

- ^Denis Roegel. 'Epact 19'(PDF). Loria.fr. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^Lichtenberg, Heiner (2003). 'Das anpassbar zyklische, solilunare Zeitzählungssystem des gregorianischen Kalenders'. Mathematische Semesterberichte. 50: 45–76.

- ^de Kort, J. J. M. A. (September 1949). 'Astronomical appreciation of the Gregorian calendar'. Ricerche Astronomiche. 2 (6): 109–116. Bibcode:1949RA...2.109D.

- ^'The Length of the Seasons'. U. Toronto. Canada.

- ^'Mean Northward Equinoctial Year Length'(PDF). U. Toronto. Canada.

- ^An act for regulating the commencement of the year; and for correcting the calendar now in useStatutes at Large 1765, with Easter tables

- ^'Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church'. Joseph Bentham. 9 August 1765. Retrieved 9 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^'Tables and Rules'. Eskimo.com. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^'merlyn.demon.co.uk'. Merlyn.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^'Inter Gravissimas'. Bluewaterarts.com. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^Gustav Teres,'Time computations and Dionysius Exiguus', Journal for the History of Astronomy15 (1984) 177–188, p.178.

- ^ abV. Grumel, La chronologie (Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1958). (in French)

- ^Peter S. Baker and Michael Lapidge, eds., Byrhtferth's Enchiridion, Oxford University Press, 1995, pp. 136–7, 320–322.

- ^Domus Quaedam Vetus, Carmina Medii Aevi Maximam Partem Inedita 2009, p. 151.

- ^Bede: The reckoning of time, tr. Faith Wallis (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999) p. xlvii, note 73.

- ^'Gauß-CD'. webdoc.sub.gwdg.de. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^Kothe, Jochen. 'Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum: Inhaltsverzeichnis'. gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^Kothe, Jochen. 'Göttinger Digitalisierungszentrum: Inhaltsverzeichnis'. gdz.sub.uni-goettingen.de. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ abReinhold Bien, 'Gauß and Beyond: The Making of Easter Algorithms' Archive for History of Exact Sciences58/5 (July 2004) 439−452.

- ^'A New York correspondent', 'To find Easter', Nature (20 April 1876) 487.

- ^Samuel Butcher, The Ecclesiastical calendar: its theory and construction (Dublin, 1877)

- ^Downing, A. M. W. (May, 1916). 'The date of Easter', The Observatory, 39 215–219.

- ^H. Spencer Jones, General Astronomy (London: Longsman, Green, 1922) 73.

- ^Journal of the British Astronomical Association88 (December, 1977) 91.

- ^Jean Meeus, Astronomical Algorithms (Richmond, Virginia: Willmann-Bell, 1991) 67–68.

- ^O'Beirne, T H (30 March 1961). 'How ten divisions lead to Easter'. New Scientist. 9 (228): 828.

References

- Blackburn, Bonnie, and Holford-Strevens, Leofranc. (2003). The Oxford Companion to the Year: An exploration of calendar customs and time-reckoning. (First published 1999, reprinted with corrections 2003.) Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Borst, Arno (1993). The Ordering of Time: From the Ancient Computus to the Modern Computer Trans. by Andrew Winnard. Cambridge: Polity Press; Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Clavius, Christopher (1603): Romani calendarij à Gregorio XIII. P. M. restituti explicatio. In the fifth volume of Opera Mathematica (1612). Opera Mathematica of Christoph Clavius includes page images of the Six Canons and the Explicatio (Go to page: Roman Calendar of Gregory XIII)

- Constantine the Great, Emperor (325): Letter to the bishops who did not attend the first Nicaean Council; from Eusebius' Vita Constantini. English translations: Documents from the First Council of Nicea, 'On the keeping of Easter' (near end) and Eusebius, Life of Constantine, Book III, Chapters XVIII–XIX

- Coyne, G. V., M. A. Hoskin, M. A., and Pedersen, O. (ed.) Gregorian reform of the calendar: Proceedings of the Vatican conference to commemorate its 400th anniversary, 1582–1982, (Vatican City: Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Specolo Vaticano, 1983).

- Dershowitz, N. & Reingold, E. M. (2008). Calendrical Calculations (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Dionysius Exiguus (525): Liber de Paschate. On-line: (full Latin text) and (table with Argumenta in Latin, with English translation)

- Eusebius of Caesarea, The History of the Church, Translated by G. A. Williamson. Revised and edited with a new introduction by Andrew Louth. Penguin Books, London, 1989.

- Gibson, Margaret Dunlop, The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac, Cambridge University Press, London, 1903.

- Gregory XIII (Pope) and the calendar reform committee (1581): the Papal Bull Inter Gravissimas and the Six Canons. On-line under: 'Les textes fondateurs du calendrier grégorien', with some parts of Clavius's Explicatio

- Mosshammer, Alden A., The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era, Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Richards, E. G. (2013). Calendars. In S. E. Urban & P. K. Seidelmann (Eds.). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac (3rd ed., pp. 585–624). Mill Valley, CA: Univ Science Books.

- Schwartz, E., Christliche und jüdische Ostertafeln, (Abhandlungen der königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. Pilologisch-historische Klasse. Neue Folge, Band viii.) Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin, 1905.

- Stern, Sacha, Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE – Tenth Century CE, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001.

- Walker, George W, Easter Intervals, Popular Astronomy, April 1945, Vol. 53, pp. 162–178.

- Walker, George W, Easter Intervals (Continued), Popular Astronomy, May 1945, Vol. 53, pp. 218–232.

- Wallis, Faith., Bede: The Reckoning of Time, (Liverpool: Liverpool Univ. Pr., 1999), pp. lix–lxiii.

- Weisstein, Eric. (c. 2006) 'Paschal Full Moon' in World of Astronomy.

How Is Easter Determined In The Orthodox Church

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Computus (Easter). |

- The Complete Works of Venerable Bede Vol. 6 (Contains De Temporibus and De Temporum Ratione.)

- (in German)An extensive calendar site and calendar and Easter calculator by Nikolaus A. Bär

- Dionysius Exiguus' Easter table

- Towards a Common Date for EasterWorld Council of Churches (Faith and Order) and Middle East Council of Churches consultation; Aleppo, Syria; 5–10 March 1997

- Text of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, British Act of Parliament introducing the Gregorian Calendar as amended to date. Contains tables for calculating Easter up until the year 8599. Contrast with the Act as passed.

- Computus.lat A database of medieval manuscripts containing Latin computistical algorithms, texts, tables, diagrams and calendars.

| Easter | |

|---|---|

Icon of the Resurrection depicting Christ having destroyed the gates of Hades and removing Adam and Eve from the grave. Christ is flanked by saints, and Satan—depicted as an old man—is bound and chained. (See Resurrection of Jesus in Christian art.) | |

| Type | Christian, cultural |

| Significance | Celebrates the resurrection of Jesus |

| Celebrations | Church services, festive family meals, Easter egg decoration, and gift-giving |

| Observances | Prayer, all-night vigil, sunrise service |

| Date | Determined by the Computus |

| 2018 date | |

| 2019 date |

|

| 2020 date | |

| 2021 date |

|

| Related to | Passover, since it is regarded as the Christian fulfillment of Passover; Septuagesima, Sexagesima, Quinquagesima, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Clean Monday, Lent, Great Lent, Palm Sunday, Holy Week, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday which lead up to Easter; and Divine Mercy Sunday, Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi and Feast of the Sacred Heart which follow it. |

Easter,[nb 1] also called Pascha (Greek, Latin)[nb 2] or Resurrection Sunday,[5][6] is a festival and holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in the New Testament as having occurred on the third day after his burial following his crucifixion by the Romans at Calvaryc. 30 AD.[7][8] It is the culmination of the Passion of Jesus, preceded by Lent (or Great Lent), a 40-day period of fasting, prayer, and penance.

Most Christians refer to the week before Easter as 'Holy Week', which contains the days of the Easter Triduum, including Maundy Thursday, commemorating the Maundy and Last Supper,[9][10] as well as Good Friday, commemorating the crucifixion and death of Jesus.[11] In Western Christianity, Eastertide, or the Easter Season, begins on Easter Sunday and lasts seven weeks, ending with the coming of the 50th day, Pentecost Sunday. In Eastern Christianity, the season of Pascha begins on Pascha and ends with the coming of the 40th day, the Feast of the Ascension.

Easter and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts which do not fall on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars which follow only the cycle of the Sun; rather, its date is offset from the date of Passover and is therefore calculated based on a lunisolar calendar similar to the Hebrew calendar. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established two rules, independence of the Jewish calendar and worldwide uniformity, which were the only rules for Easter explicitly laid down by the council. No details for the computation were specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and generated a number of controversies. It has come to be the first Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon that occurs on or soonest after 21 March.[12] Even if calculated on the basis of the more accurate Gregorian calendar, the date of that full moon sometimes differs from that of the astronomical first full moon after the March equinox.[13]

Easter is linked to the Jewish Passover by much of its symbolism, as well as by its position in the calendar. In most European languages the feast is called by the words for passover in those languages; and in the older English versions of the Bible the term Easter was the term used to translate passover.[14]Easter customs vary across the Christian world, and include sunrise services, exclaiming the Paschal greeting, clipping the church,[15] and decorating Easter eggs (symbols of the empty tomb).[16][17][18] The Easter lily, a symbol of the resurrection,[19][20] traditionally decorates the chancel area of churches on this day and for the rest of Eastertide.[21] Additional customs that have become associated with Easter and are observed by both Christians and some non-Christians include egg hunting, the Easter Bunny, and Easter parades.[22][23][24] There are also various traditional Easter foods that vary regionally.

- 3History

- 3.2Date

- 4Position in the church year

- 5Religious observance

- 7Easter celebrations around the world

- 11External links

Etymology

The modern English term Easter, cognate with modern Dutch ooster and German Ostern, developed from an Old English word that usually appears in the form Ēastrun, -on, or -an; but also as Ēastru, -o; and Ēastre or Ēostre.[nb 3]Bede provides the only documentary source for the etymology of the word, in his Reckoning of Time. He wrote that Ēosturmōnaþ (Old English 'Month of Ēostre', translated in Bede's time as 'Paschal month') was an English month, corresponding to April, which he says 'was once called after a goddess of theirs named Ēostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month'.[25]

In Latin and Greek, the Christian celebration was, and still is, called Pascha (Greek: Πάσχα), a word derived from Aramaic פסחא (Paskha), cognate to Hebrew פֶּסַח (Pesach). The word originally denoted the Jewish festival known in English as Passover, commemorating the Jewish Exodus from slavery in Egypt.[26][27] As early as the 50s of the 1st century, Paul the Apostle, writing from Ephesus to the Christians in Corinth,[28] applied the term to Christ, and it is unlikely that the Ephesian and Corinthian Christians were the first to hear Exodus 12 interpreted as speaking about the death of Jesus, not just about the Jewish Passover ritual.[29] In most of the non-English speaking world, the feast is known by names derived from Greek and Latin Pascha.[4][30] Pascha is also a name by which Jesus himself is remembered in the Orthodox Church, especially in connection with his resurrection and with the season of its celebration.[31]

Theological significance

The New Testament states that the resurrection of Jesus, which Easter celebrates, is one of the chief tenets of the Christian faith.[32] The resurrection established Jesus as the powerful Son of God[33] and is cited as proof that God will righteously judge the world.[34][35] For those who trust in Jesus' death and resurrection, 'death is swallowed up in victory.'[36] Any person who chooses to follow Jesus receives 'a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead'.[37] Through faith in the working of God those who follow Jesus are spiritually resurrected with him so that they may walk in a new way of life and receive eternal salvation, being physically resurrected to dwell in the Kingdom of Heaven.[35][38][39]

Easter is linked to Passover and the Exodus from Egypt recorded in the Old Testament through the Last Supper, sufferings, and crucifixion of Jesus that preceded the resurrection.[30] According to the New Testament, Jesus gave the Passover meal a new meaning, as in the upper room during the Last Supper he prepared himself and his disciples for his death.[30] He identified the matzah and cup of wine as his body soon to be sacrificed and his blood soon to be shed. Paul states, 'Get rid of the old yeast that you may be a new batch without yeast—as you really are. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed';[40] this refers to the Passover requirement to have no yeast in the house and to the allegory of Jesus as the Paschal lamb.[41]

History

Early Christianity

The first Christians, Jewish and Gentile, were certainly aware of the Hebrew calendar.[nb 4] Jewish Christians, the first to celebrate the resurrection of Jesus, timed the observance in relation to Passover.

Direct evidence for a more fully formed Christian festival of Pascha (Easter) begins to appear in the mid-2nd century. Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referring to Easter is a mid-2nd-century Paschal homily attributed to Melito of Sardis, which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.[42] Evidence for another kind of annually recurring Christian festival, those commemorating the martyrs, began to appear at about the same time as the above homily.[43]

While martyrs' days (usually the individual dates of martyrdom) were celebrated on fixed dates in the local solar calendar, the date of Easter was fixed by means of the local Jewish[44]lunisolar calendar. This is consistent with the celebration of Easter having entered Christianity during its earliest, Jewish, period, but does not leave the question free of doubt.[45]

The ecclesiastical historian Socrates Scholasticus attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the perpetuation of its custom, 'just as many other customs have been established', stating that neither Jesus nor his Apostles enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. Although he describes the details of the Easter celebration as deriving from local custom, he insists the feast itself is universally observed.[46]

Date

Easter and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts, in that they do not fall on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars (both of which follow the cycle of the sun and the seasons). Instead, the date for Easter is determined on a lunisolar calendar similar to the Hebrew calendar. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established two rules, independence of the Jewish calendar and worldwide uniformity, which were the only rules for Easter explicitly laid down by the Council. No details for the computation were specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and generated a number of controversies. (See also Computus and Reform of the date of Easter.) In particular, the Council did not decree that Easter must fall on Sunday. This was already the practice almost everywhere.[48][incomplete short citation]

In Western Christianity, using the Gregorian calendar, Easter always falls on a Sunday between 22 March and 25 April[49] inclusive, within about seven days after the astronomical full moon.[50] The following day, Easter Monday, is a legal holiday in many countries with predominantly Christian traditions.